Over the past 136+ years, Portland Fire & Rescue’s primary mission has shifted from fighting fires to responding to public health and safety emergencies. This lower demand for fire response is due to advances in fire-resistant building materials, and an increased need for emergency responders. With their stations distributed evenly across the city, firefighters are well-positioned to rapidly respond to emergency calls, which are mainly comprised of medical emergencies.

In 2019 they partnered with The Social Impact Lab, which runs workshops with community members and organizations to solve problems using design thinking methods. I’m a volunteer facilitator for the Social Impact Lab, but this season I decided to participate in the workshop to help with the project and get a better sense of the participant experience.

In this article, I’ll talk about how we used an approach based on design thinking methods to help Portland Fire & Rescue explore ways they might respond to their changing mission.

Identifying a Problem

At the project kickoff, Portland Fire & Rescue (PF&R) told us about a recurring problem that was causing stress on the system – repeat calls to 911 for issues that do not require immediate medical attention. For example, if someone calls 911 and complains about stomach or lower back pain, that triggers an emergency response that includes a fully-equipped fire crew. Upon arrival, firefighters may find that the issue could have been resolved minimal treatment with over the counter drugs.

These calls happen so frequently that they’re given a name; low acuity emergency calls. They are a large source of stress for the caller, the firefighter, and everyone else involved. PF&R learned from their call response records that these calls were primarily coming from the homeless and high-risk communities.

Between 2000 and 2017, the call volume for Portland Fire and Rescue increased by 23%; the majority of this growth came from “medical” and “other” calls rooted in non-fire causes.

Portland Fire and Rescue Blueprint for Success – FMA 11 Lents

To make sure our solutions would meet the goals outlined in the Blueprint for Success we needed to view this problem through the lens of PF&R’s intent to be a community resource. Working with stakeholders from PF&R, we identified three problem areas that we believed would deliver on those goals while addressing the problem of low-acuity calls:

We formed three teams of three, and my team decided to focus on the first design challenge: how might we use existing community assets to address risk factors specific to high-risk, vulnerable populations or areas?

Limits are good

We would have six working sessions to complete a design-thinking focused process and present potential solutions. The workshop leader made it clear that we were not expected to redesign of the fire department or solve homelessness in that time. We were asked to keep in mind the limited time and resources of firefighters and the fire department. We were assigned to look specifically at Fire Management Area (FMA) 12, which serves a large section of Northeast Portland, just south of the airport.

Research round-up

I started by researching existing solutions to similar problems. Competitive research (not that we were in competition with anyone) seemed like the right place to start so we could avoid repeating what was already being done. This research also helped us learn about the problem space, so we felt more confident approaching users in the next phase of research.

These resources proved to be the most helpful over the course of the workshop:

- Portland Fire & Rescue’s Blueprint for Success reports that identified key areas where firefighters could make an impact: community safety, housing/resources, mental health, public health, and racial equity.

- PF&R’s call response metrics

- The proposal by Street Roots for a Street Response Team

- A lecture on homelessness at the Oregon Health Forum

Learnings

There are many organizations working on related problems.

The Joint Office of Homeless Services funds around 40 programs that work to fight homelessness. The Office of Civic Life and Portland’s neighborhood associations, and many other nonprofits are working on problems that could improve outcomes for these emergency calls if they were solved. It was clear that any solution we would present should involve the organizations that were working with people who are experiencing or are at risk for, homelessness.

One example that stood out was the Portland Street Response program, which was being developed at the time of the workshop. Originally suggested by an editorial in Street Roots, the program would create teams of first responders that were less resource-intensive than a team of firefighters – smaller vehicles that could be dispatched quickly. These might include people with social work skills along with EMTs who would be better suited to handle individuals with mental health disorders and low-acuity emergencies.

One of the best ways to prevent low acuity calls is through regular check-ins.

As luck would have it, Fire Station 12 had been working on a program that addressed this very issue. Through the CHAT program, firefighters identified all of the individuals who frequently called 911 in their service area and started checking in on them regularly. Doing so reduced 911 calls by 50%.

Interviewing the community

Now that we knew who was working on the problem, we decided to reach out to community members and organizations so we could identify what was missing from these solutions.

To learn more about what the community knew about the health and safety resources available to them, we focused our questions on two areas:

- What are the resources available to a community member?

- What is their mental model of those resources and services?

Our team then interviewed community members, city leaders, and non-profit workers.

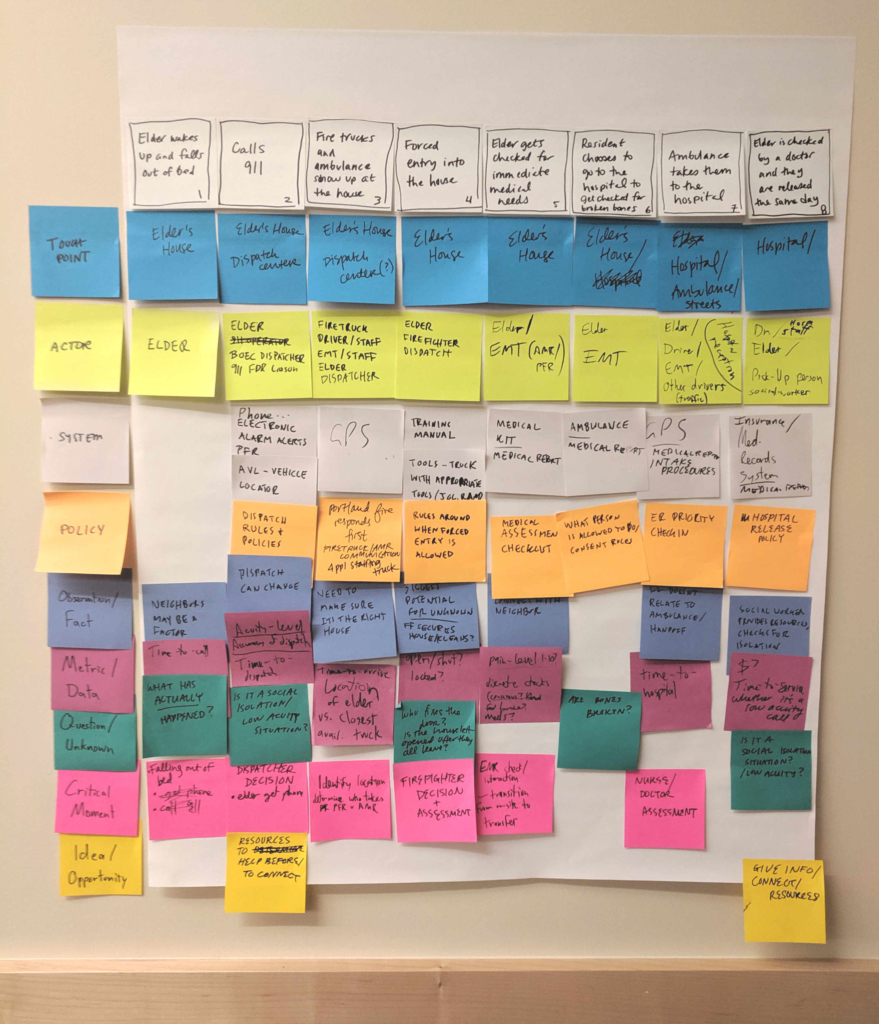

We also wanted to get a better idea of the firefighter’s experience. The workshop leadership brought in a service design professional to help us create a service blueprint for an emergency call. We accomplished this in collaboration with stakeholders from Portland Fire & Rescue who walked us through a common scenario and answered our questions.

Learnings

Outreach makes a huge difference, but there isn’t enough funding.

One-on-one check-ins for people at risk of homelessness are highly effective. When someone is given personal attention and put on a track to getting the help they need, they are less likely to call 911 for non-emergency help. But while there are many groups working on homelessness, most are underfunded relative to the scope of the problem. There just isn’t the budget to hire social workers for this level of outreach.

Community members want to help each other but aren’t sure of the best way.

People want to help others who seem like they are in trouble. But these potential helpers are held up by uncertainty. Community members reported fears of getting into legal jeopardy, confusion about when to call 911, and worries about interfering where they aren’t wanted or needed.

“It’s the ‘knowing’ if I should help that holds me up a lot. I don’t know what your problem is. I can guess and judge, but maybe it’s not a problem for you and I don’t want to go fixing things that aren’t your problem.”

– Community member

Firefighters are extremely well-positioned to deal with emergencies, but not to prevent them.

Many people might be involved in one call: 911 dispatch, firefighters, EMTs, police, neighbors, to name a few. Once the call is complete, the affected individual is usually in the hands of a hospital, and possibly a social worker. In the case of the repeat low-acuity calls, the firefighters don’t have a way to track or improve outcomes. They can only respond again the next time the individual calls.

Brainstorming solutions

Using the research we’d gathered, all of the workshop participants collaboratively brainstormed potential ideas based on all of the research done so far. From this, each team member developed a separate hypothesis that they would use as a catalyst for a potential solution.

My hypothesis was that stronger connections between neighbors can improve their collective knowledge of health and safety resources. With that knowledge, a community can empower individuals to help prevent issues that lead to common non-emergency calls.

Testing the hypothesis through a community survey

Would individuals be willing to reach out for help, or offer it? What would their decision-making process look like? To answer these questions and test the assumptions that came out of our hypothesis, I asked a few community members questions about safety, health, and their willingness to respond to emergencies. I framed these questions in a scenario that I presented to five community members.

If 911 didn’t exist, what would you do in the following situations:

- You were feeling very sick, but weren’t sure if it was an emergency?

- You saw a dog locked in a hot car?

- You haven’t seen an elderly neighbor for a few days, and you knew they had trouble getting around?

Learnings

The goal of this exploratory survey was to probe the hypothesis for potential insights. The responses provided some interesting feedback:

- All but one participant did not know a neighbor that they could rely on in the case of an emergency..

- All would look to local businesses as the first resource for information.

- All validated that fear of legal jeopardy and/or interfering in someone else’s life were potential blockers to taking action.

A proposed solution: connect the community to fill the prevention gap

Based on everything we learned I believed there was an opportunity to prevent some emergency situations by training community members to identify health and safety issues, and empowering them to act on behalf of their neighbors before those issues become an emergency.

I proposed that we create a network of neighborhood “inreach” volunteers who would regularly collect and share knowledge of available health and safety resources with the community. This solution will allow communities to define themselves and their own needs. Communities with a high population that is at risk for homelessness will have different needs than a community of elderly retirees. The volunteers will tailor their resources to their community.

Using scenarios to define the solution

What would this look like in practice? Here are a few scenarios where community members could help fill a prevention gap:

For someone moving into a new community, a community member acts as a “concierge” by reaching out to them and providing useful information on how to get help if they have health or safety needs.

For a community member who has called 911 multiple times over the past few weeks, Portland Fire & Rescue reaches out to the network of neighborhood concierges to ask if a neighbor is available to check-in for the next couple of days.

For a business owner worried about potential crime from a nearby homeless camp, the community concierge connects them with a local homelessness advocacy group to help facilitate a conversation.

For a community member who is at risk for homelessness, the concierge would connect them with an organization that provides the resources they need, whether that’s food assistance or job support. The concierge can also connect them with others who have been in similar situations for advice.

Follow-up is key to all of these scenarios. The concierge and community member should have the ability to follow-up and regularly check in with one another.

Building a service

This solution would be a new service; the city government would provide tools and training, while community members would work as volunteers to develop their health and safety resources and identify needs.

Phase I: Identify and engage a community

In a given neighborhood, community members would set up a pop-up community center to ask their neighbors about the health and safety resources that are available to them. A facilitator from a government agency, such as Portland Fire & Rescue, would identify a space and provide a set of activities to help community members tell their stories.

Some activities we could run include:

- Mapping available health and safety resources against areas that feel safe or unsafe

- Surveying community members to assess:

- How comfortable would they be with identifying and acting upon potentially preventable emergencies?

- If they were in trouble, what help would they be willing to accept from their neighbors, if any?

Phase II: Create a network of neighborhood “concierges”

The program organizers would use the information they collect during the pop-up community centers as training material for people willing to act as neighborhood concierges. The city could model this program after (or even add it as a new training module to) the Neighborhood Emergency Teams, who currently act as safety officers in the event of a catastrophe.

The goal of the neighborhood concierges would be primarily preventive and social. They would achieve that by:

- Continuously learning and sharing the community’s stories

- Identifying neighbors in need and directing them to the right resources

Phase III: Create a rapid response network

To make this a citywide solution, we would build a network that helps neighborhood concierges share resources across communities. This would allow those volunteers to quickly ask other concierges for help when they find a potential problem. It could follow the model of 15th Night, a rapid access network being built in Eugene to keep youth from staying on the street for more than 15 nights (after which they are statistically more likely to become chronically homeless) by connecting them to those who could help provide rides, meals, housing, and other resources.

Next Steps: Prototype and test

To test this prototype, PF&R would identify a community and run pop-up community centers on a bi-weekly basis for 2-3 months. During these, they would ask community members about their willingness and ability to handle health and safety issues. They would also collect names of potential volunteers and start a knowledge base to share back with the community.

In order to iterate quickly, each pop-up community center session would change in response to the outcomes of the previous one. At the end of the prototype session, we would review the process with city stakeholders and volunteers to determine if it’s viable to start training neighborhood concierges.

Assumptions to test

- Community members will be willing to give enough of their time to make an impact.

- Some people will be more helpful to have in this network than others – social workers, doctors and nurses, firefighters, community advocates.

Questions to test

- Can we provide access to local resources in a way that respects privacy?

- How can we identify those in need without stigmatizing them?

- How can we connect those in need with the right services before they call 911?

- Will this actually reduce calls?

Summary

The goal of this solution is to encourage conversations between neighbors around health and safety. These can be difficult conversations, but the more we engage in them, the stronger our communities will be. It must recognize that there is no “done” when living in a community. Stories need to be retold and relearned as the people and places change. Any solution has to be flexible enough to grow and change with the community it serves.